- Home

- Marc Phillips

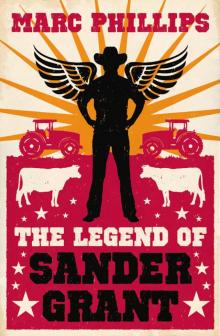

The Legend of Sander Grant Page 6

The Legend of Sander Grant Read online

Page 6

‘It would seem that God’s making a point, wouldn’t it? I mean, He’s wiping us out, and it’s not mentioned in passing. Three whole verses begin, respectively, “And all flesh died that moved upon the earth ...” then “All in whose nostrils was the breath of life ...” so on and so forth ... “died” and one more time, for good measure, “And every living substance was destroyed ...”’ He paused. ‘Is Moses trying to tell us something here?’ Roger turned to the board and wrote:

Man – mistake?

‘But then, why not have Noah load the animals on the boat, nail the door shut and cast that sucker off? Why save a few of us? That sounds like me when I was trying to give up smoking. I’d toss out every Chesterfield in the house. Get thee rid of those nasty cancer sticks and be quit of it forevermore! Except that pack in the nightstand.’ Sander heard guffaws in agreement, saw heads nodding. Roger shrugged.

For some reason, this folksy, proletariat approach to the subject matter of divine wrath struck Sander as flippant. True, Roger was reaching his people and Sander hadn’t witnessed a more natural teacher. Regardless, he felt like challenging the man. All of the preachers, pastors, reverends, rectors, and priests he’d seen had earmarked passages relevant to the day’s message. Some, like Roger, had even gone to the trouble of memorizing a few verses. That only meant they did a little homework last night. It evidenced no understanding.

Roger was saying, ‘... so mankind might not actually be a mistake in God’s eyes. You think? Maybe there were just some bad ones in the bunch?’

This guy never gives any answers, Sander thought, and he boomed, ‘Maybe He just killed the ones He really hated.’ He didn’t expect his voice would carry quite so well in the little space. It startled several people, Jason seemed to draw away from his side, and Sander was sorry for that. He continued, more softly, with a question of his own. ‘Does a perfect being hate?’

‘No, Sander. I would say not.’ Roger pointed his chalk at Joyce the cook, who sat on the first row. ‘You’ve got better eyes than me, hon. Could you read for us from Malachi?’ Sander noticed then that, bad eyes notwithstanding, Roger carried no Bible.

Joyce found Malachi and asked, ‘Which chapter?’

‘Just start from the beginning, please.’

‘“The burden of the word of the Lord to Israel by Malachi,”’ read Joyce. ‘“I have loved you, saith the Lord. Yet ye say, Wherein has thou loved us? Was not Esau Jacob’s brother? saith the Lord: yet I loved Jacob, And I hated–”’ She broke off and all was quiet save a dripping faucet in the kitchen. Which one of them was the plumber, again?

‘Is that what you’re talking about, Sander?’

‘That’s one spot.’

‘Yeah,’ Roger nodded, ‘a personal favorite. Keep reading, Joyce.’

‘“And I hated Esau, and laid his mountains and his heritage waste for the dragons of the wilderness.”’

‘Okay. Thank you.’ Roger turned to the board and wrote:

God hates

The declarative sentence pleased Sander.

‘Not only does He hate,’ Roger said, ‘but, according to the following verses, He carries on with His indignation forever. An unforgiving, divine hatred. Oh, and God says there are dragons. Not something we’ve ever discussed before. By show of hands, who thinks there were dragons back then?’ Roger let that dangle before them and nobody dared touch it. ‘Then again, how much of the Bible did God actually write?’

‘I can’t find any of it written by God,’ said Sander.

‘Well,’ said Roger, tapping ‘God hates’ on the blackboard, ‘we know Malachi wrote that part. His byline is right up top. So it starts out as hearsay and we cannot be sure how it’s been changed, edited, and pieced together since.’ He took Joyce’s Bible and held it up. ‘For the purpose of knowing God, though, is this all we’re given?’

‘The world and all that’s in it,’ somebody said. Sander couldn’t tell who.

‘Now we’re talking.’ Roger scrawled those words on his blackboard and underlined them. ‘So let’s ask ourselves how perfect a place this is, and extrapolate from there something about the being who made it. Why don’t we start with childhood cancer and nuclear weapons? They’re as good as dragons and everlasting hatred, and we know for sure they exist. But,’ he said, ‘before we go too far down that road, I want to caution you; God doesn’t appreciate armchair criticism. Unless you know of someone who could’ve done it better.’

On the board, he wrote:

War Plague Crime Oppression

He said, ‘There’s a sizeable part of our world. And that’s either downright meanness, or somebody messed up somewhere.’

Confusion befell the congregation and Roger had them. Now, unlike when they walked in here, they actually required some answers in order to carry on. None of these people, Sander thought, would leave here now if the building were ablaze. Their faith was laid bare.

Roger told them, ‘It’s the first thing God admits to us, the fallibility of omnipotence. He tells us that omnipotent, omniscient, and ubiquitous aren’t synonymous. They’re not even distant cousins. He tells us this to prepare us for what’s left to do – what we have to deal with.’ He counted them off on three fingers, ‘All-powerful, all-knowing, and ever-present. That would be quite a feat, the ultimate hat trick. But two out of three aint bad. Once upon a time, the Greeks knew this about their Gods, that mistakes were sometimes made. And they revered and worshiped them all nonetheless. Somewhere along the line, we decided that wasn’t good enough. We had to make our God into something He never claimed to be – perfect.’ He held the Bible up once more, ‘We just haven’t expunged all the evidence to the contrary. Give us time. Meanwhile, we knew right off, if God was to be perfect, we had to have somebody else to blame for all this other inconvenient stuff. Who could we pin it on?’ Roger took a long look at the blackboard and scratched his chin with the leather spine of Joyce’s King James. ‘And if we pin it on somebody else, would he not be of God’s hand as well?’ Turning to his congregation, ‘Gets tough when we start playing with the facts, don’t it?’

He extended Joyce her Bible and she checked it for injury while he switched gears and continued.

‘Which brings me to the second thing God wants us to know. He didn’t write that book. Didn’t even endorse it. But much of it, even in its corrupted form, is gospel. And – listen carefully to this – those parts which are not strictly accurate can tell us just as much as credible history. If we know the difference. So let’s talk about how we parse this thing for truth, that we might see what’s offered by the rest.’

Sander checked his watch when the lecture was done. He would not call this a sermon because that term demeaned it. It had lasted nearly two hours. Jason said he and some of the congregation were staying to cook a meal, but Sander told him there was work at the ranch that he needed to get done.

‘I’ll call you later,’ said Jason, and made his way to the kitchen as Sander left.

Roger caught Sander at his truck in the lawn. ‘Not hungry?’ he asked.

‘I’m always hungry, but my mother will have something ready and I’ve got to get back.’

‘Did you enjoy the meeting?’

‘It was different. Thanks for scooting the pew back for me.’

‘We didn’t scoot anything. It was built that way, bolted to the floor like the rest. Tell me something. When did you discover that your people were in the Bible?’

This shocked Sander and he fought not to show it. ‘I’m not sure it’s talking about my people.’

‘I think you’ve got more than a passing suspicion. When did you read it?’

‘I started a few months ago. Finished recently. One thing I am suspicious about, though. Is it God who wants us to know He had nothing to do with the Bible, or is it you?’

Roger nodded and looked at his scuffed loafers. ‘I didn’t say He had nothing to do with it, but I’m not positive He was, let’s say, enthusiastic about today’s talk. Overall.’

‘Why didn’t you ask Him?’

‘It’s easier to apologize. He’ll stop me if I go too far.’

‘Well, since God didn’t write the stuff, and we’ve now discovered it’s inaccurate, I’m not going to spend much time searching for any of my relatives in there.’

‘Makes good sense. Until you ask yourself what kind of hereditary trait might persist for hundreds of years, never skipping a generation. How dominant would that gene need to be?’ Roger seemed to ponder his own question for a few seconds. Then he turned and saw several members of the congregation standing on the porch, looking at them. ‘You should talk to someone about what you’ve read, someone who’s studied the text at length. Knowledge always helps and never hurts, though it may be painful.’

‘Talk to you, you mean.’

‘I hold a Doctor of Theology from Harvard. Various degrees in history, archeology, yada-yada. My resume, in short. Makes me sound like a pompous ass, I know. I’d be honored to help you, but there’s a lot of smart people out there. Just make sure whomever you speak to has what you’re looking for, right? And not some superstitious bullshit. Have a good afternoon, Sander. Thanks for stopping by.’

‘You too.’ It was all Sander could think to say.

As he started the truck, Roger trotted back over. What now, thought Sander. He didn’t know how much more he could process today. He rolled down his window.

‘Almost forgot.’ Roger handed him an envelope from his coat pocket. ‘I’ve been saving this for you. Give it a read when you get some time. And I hope it goes without saying that your entire family is welcome here.’

‘Thanks.’

Sander tucked the envelope into his back pocket without a thought. On the drive home, he concentrated on finding one thing Roger Carlson had said that he disagreed with. It would be much easier to distrust him, to doubt him, to dislike him, at least a little. He parked in front of the gate back home. Lunch was ready and on the table. He ate with his parents and waited for the questions. When none came, he excused himself and went upstairs to change into his work clothes.

Folding his pressed jeans, he found the envelope tucked into the back pocket and sat on his bed to open it. There was a single word on the outside: Nephilim. Inside was a Xerox copy of a newspaper article. It was old, blurry in places, and Sander had to squint to read.

New Castle News

Monday September 15, 1913

Vera Townsman Unearths a Giant Frame of

Murdered Cattleman in Oklahoma

BARTLESVILLE: – Early days in what was formerly Indian Territory are being recalled by the discovery of the skeleton of a man unearthed at Vera, this county, a few days ago, not to mention many relics such as revolvers, parts of rifles used years ago, that are also being found. For, a quarter of a century ago on this side of the state, especially in Washington County, scores of crimes were committed and many a man was sent to his grave, buried in the wilderness and one more life was added to the long list of tragedies that gave Indian Territory a national reputation as the home of bad men. Civilization, though, has changed conditions and no longer do ‘bad men’ travel over the prairies unmolested.

Just the other day a Vera resident was digging a foundation for a house. Three feet beneath the surface he found the skeleton of a man. The bones indicated that the victim of a knife or a revolver was a large man. Oldtimers in Vera recalled that about a quarter of a century ago a cattleman suddenly disappeared. It was thought he had gone west, although he had made no provisions for his property and had never indicated he intended leaving. Now it is believed the human skeleton just found was that of the cattleman who disappeared a quarter of a century ago.

At the bottom, Roger had written, ‘Do you know who that cattleman was?’ Sander stared at it for a moment. There was no name in the article, so of course he didn’t know who it was. Nor did he know anyone named Nephilim. He put the paper back in the envelope, the envelope in his Bible and shoved it under his bed. He knew there was hard work outside that could wait no longer.

Beyond the gate, Dalton stood by the bay door at the barn, gloves in hand.

‘I thought you’d already have the tractor out there,’ said Sander. ‘Is it broke?’

‘It aint broke. I’m waiting on Javier. Said he’d be here after lunch. I thought we’d let him drive while you and I load together. Some quality time, I think is what they call it.’

Dalton looked Sander up and down. Lately, the worry and the work and the unforgiving minute had robbed him of a long overdue appraisal of his boy. Sander hadn’t shaved this morning, that’s the first thing he noticed. The stubble on his brick of a jaw had a red tint to it, but not so much that it didn’t match his brown hair. Dalton was slouching against the barn, but he estimated that if he stood erect – and he resisted the urge to do so – his head wouldn’t top Sander’s but a few inches. His son would be ten feet tall in a year. Their hands were the same size. Sander’s feet were already bigger. His shoulders wider. He needed some meat on his arms and back, but he was likely within a hundred pounds of Dalton’s weight.

‘What did the preacher man have to say?’

Sander shook his head. ‘Said little people were a bad idea.’

They laughed.

‘Well,’ said his daddy, ‘I guess you can’t get everything right.’

‘Said that, too.’

‘I heard you and Jason–’ He started again, ‘I wasn’t snooping on you. Walking by in the hall I heard you and Jason talking about selling some of your work.’

‘Yeah. He thinks it’s time.’

‘You?’

‘I’m not sure yet. Jason says he knows of buyers for my style and he’ll make the introductions. Better than having to do a show and all.’

‘It would be,’ Dalton agreed, ‘but might not get you the exposure, if that’s what you’re looking for.’

‘Not so much. If I could just bring in a little money, that’s all I’m after. Clear out my studio a bit and help out with the bills. Besides, if I were to show up at a gallery over in Tyler or Dallas, the whole thing would be about me. A freak show. Better that the art goes its own way without me, is what I mean.’

‘Don’t call us freaks, boy.’

‘I didn’t. They would.’

‘Hell with them. But,’ said Dalton, ‘there aint no way you’re gonna keep yourself a secret. They’re gonna come looking.’

‘I guess they will. It’ll pass. And like I said, it’s money. Jason says I should price my bigger pieces in the five-hundred dollar range.’

‘I’m no judge of art, but I’ve got eyes. From what I’ve seen, Jason’s on the low side. You’re good. Your stuff is special and I’m proud of you.’

‘Thanks, dad.’

‘And if I see one dollar of that money paying ranch bills, I’ll whip you till you can’t sit down. That’s your money and I want you to save it, you hear?’

Nothing.

‘You hear?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Yonder comes Javier. Let’s throw some hay.’

Dalton stood and gave Sander a shove. The boy didn’t budge.

‘Keep up long as you can,’ Sander said, ‘but when you get winded, go ahead and sit down. I don’t want you to hurt yourself.’

‘Right.’

They were putting on their gloves as the Mexican ranch hand walked up between them. When Dalton fished the tractor key from his pocket and dropped it in his hand, Javier looked like a beggar kid on the streets of a border town. The flatbed trailer was already hitched to the New Holland and Javier wasted no time in pulling it around the barn and heading east to the rows of bales. Father and son trotted over and jumped on the trailer for the ride.

The tractor stopped at the south corner of the hayfield. Javier idled the engine. Dalton surveyed the two hundred acres. Geometric rows of round bales, spaced ninety feet apart. This was hay they knew they would sell. The last growing season had been a short one and their meager budget allowance for fertili

zer of late meant the crude protein content wasn’t nearly what Grant stock required. Which also meant these bales were light, about five hundred pounds apiece.

‘Wasting daylight,’ Dalton said.

In the past, Sander had always been the catcher. He stayed on the trailer, situating each new bale against the last as Dalton heaved them up, three high.

Today, he said, ‘Take it easy. Let me throw some.’

‘Get after it,’ his daddy told him as he stood on the flatbed and motioned Javier ahead.

The weight of the first few caught Sander by surprise and Dalton saw it. He didn’t offer any help, only motioned for Javier to slow a bit off the pace they were accustomed to moving. By the end of the first row, Sander had figured out how to use his legs to get under the bales, then rotate his trunk to let the weight carry itself from his arms. Sort of bellying the bales over. Problem was, in the middle of the second row, he now had to throw the things on top of the first layer, another five feet up, at least. He could feel his heartbeat all the way down in his thighs and it was increasingly difficult to catch his breath between bales. He began to wonder if he was doing it much faster than a little tractor with a hay spike.

Dalton stood atop the hay, feet spread for balance, looking like the Colossus of Rhodes waiting for something to do. Sander no longer believed he had the vaguest notion of his father’s strength. Even his gloves were drenched with sweat. If he stopped to suck wind, hands on his knees, he had to run to catch the tractor again. Still Dalton made no move to assist, didn’t bend to grab the netting of a single bale. He wanted to see if Sander would quit.

When the second layer was solid, Dalton hollered for Javier to stop. He hopped off the trailer and patted Sander on the back.

The Legend of Sander Grant

The Legend of Sander Grant