- Home

- Marc Phillips

The Legend of Sander Grant Page 2

The Legend of Sander Grant Read online

Page 2

He would hire professionals from Elgin Breeding Service over in Bastrop County. The best in the business. He would pay whatever to have them come here and teach him how to collect the semen, and he would watch them every second. He would have them recommend a freezer and all the equipment needed to keep it safe and viable. Every drop accounted for in the books. He felt he only needed to say once that he would not, under any circumstance, sell the Grant bloodline, but the fact was, these past few years, disaster had come too close for comfort. He was sure he could keep a dozen heifers alive no matter what, worse come to worst, and if he had some semen stored, he could always start over.

The major risk was theft. Grant Beef brought nearly triple the price of common stock. It was gold on four legs. People had long since been trying to steal a young bull from their pastures, especially during Will’s day. Back then, horsemen riding the fence line with rifles numbered as many as all the other ranch hands combined. Not as much a worry these days, but the bulls were still kept in the center of the spread. Then again, semen is roughly four hundred and ninety-seven pounds lighter than one of their weaned calves. He had taken all this into consideration. The storage facility would be a vault. There would be one key, which he would eventually hand over to Sander.

That was it. Dalton’s considerable thinking on the subject, in short. He waited. The wind shifted and blew his hair into his face. He thought he might need to add more about how perilously close he had come to pissing away the legacy. Maybe frame some of his ideas as questions. He suddenly felt disrespectful and insubordinate.

Will said, ‘He’s quite a boy. You done good, son. And a family name you gave him. Thanks for that. Your mother would be so proud. He looks like Sandy’s father, you know it?’

‘Yeah. The name was Jo’s idea. She wouldn’t have it any other way. She likes us.’

‘She takes good care of you?’

‘Yes daddy, she does.’

‘She’s a fine woman.’

‘The best.’

‘But she scares hell out of me sometimes.’

‘Me too.’

Then his father told him, ‘You’ll do what you think is best to keep the herd. I wouldn’t have left it to you if I didn’t trust that. Stand strong. Bring my grandbaby to see me.’

‘Yes sir. When he’s ready.’

2

The world awaiting Sander at Gardner Elementary School was not the one he expected. His parents did not discuss it with him at length, so he had no basis to expect anything. Since when, though, does a child need any basis to see a future of his making?

As the end of summer approached and the first day of kindergarten along with it, Jo would bring up the subject when they were alone. This was odd and uncomfortable to Dalton, her asking for his thoughts on this stuff. He preferred Jo rule the house and matters thereabout in the manner which had thankfully become her custom, as an unyielding matriarch, benevolent but noticeably absent due process. This, he was certain, was the bedrock of their strength as a family. Meanwhile, he plied the land which fed them, his domain and birthright, with fathoms of understanding from Grant generations before him and, on occasion, with arms that could nudge a hillside back in line when it was justified. It seemed the proper order of things. The vestiges of medieval order hadn’t faded so much among Dalton’s people. They had always served at the behest of their Queen.

The first time his wife said, ‘I have no idea how to prepare him for this, do you?’

He told her, ‘I only have the one child too, Jo,’ and he kept his further opinions on the subject to himself.

He could feel she was already seeing, thirteen years down the road, the boy graduating in cap and gown, with smiles, tears, Pomp and Circumstance. She was trying to anticipate all the bumps and hurdles along that road. Dalton didn’t envision such a long journey. Graduation hadn’t proven workable for him. He ended his public schooling in the fourth grade – when he was seven feet tall – and his maternal grandmother took up that part of his education. His father taught him other things. Conformity issues tended to sort themselves out as they saw fit and, in his experience, it had not made any difference what worrying he applied.

But later, lying beside him in their bed, she wanted to know, ‘What was it like for you?’

‘Strange,’ he said, ‘but not unpleasant.’

‘How did your dad– What did he say to you when you were starting school?’

‘Grandma said I would do well in whatever I tried, and daddy told me not to get it in my head that school meant I didn’t have to do my chores anymore.’

‘Is that what you intend to say to my boy?’

‘I hadn’t intended to say anything. He already knows as much, just like I did. I wish you wouldn’t fret so much over this. He’s a good person. People will like him. They’ll want to keep him, and he needs to feel that.’

Jo sat bolt upright and turned on the lamp. ‘Well they can’t have him.’

When he didn’t respond, she said, ‘They can’t have him. Do you understand me?’

‘Yes. He’s yours, honey.’

But that was not nearly enough reassurance. So, when the first morning of school came, Sander’s mother left him with some choice words of her own to recall.

‘Come back to me.’

‘I will, mamma.’

Sander brought home his stories of this new place as though none had been there before him and Jo studied her boy carefully as he regaled her. Mixed with his wonder and curiosity were traces of disappointment. The selfish part of her reveled in that. The majority of her wanted more for him, wanted him to like it too much, for a while at least. It was a month before Ms Moffit called the house.

‘He’s a real treat to have in my class, but he’s terribly bored, Mrs Grant. I try to spend time with him, answering his questions and giving him things to do, but it takes away from time I should be spending with the rest of the kids. It’s not fair to him or them.’

‘What do we do, then?’

‘I spoke with the counselor and the principal. Sander’s test scores are high enough to bump him to the first grade, but his emotional development is more second-grade level. Could you and your husband come in for a conference?’

‘Yes. I can, anyway.’

‘Also. You should know this. Your boy has a tremendous talent for painting. You might think of having someone more knowledgeable than me look at his work.’

So Sander finished that year in the first grade and this started a pattern of skipping a grade every so often – when the boredom threatened to return – that would follow him throughout grammar school. At first, the obvious practical difficulties with this were addressed by the school counselor, who came up with the idea of sending Sander home for the summer with the books from the grade he would likely skip. She told Jo that the things children learn in the lower grades are not difficult to master. They spread them out over several years to keep pace with the maturity level of average children, their attention spans more than their aptitude. Sander had plenty of attention to give, she said, and it shouldn’t take much of Jo’s time to prepare him to skip the early grades. However, she suggested a summer tutor once he passed grade six.

It worked wonderfully for a good while. Sander was a blissfully happy four-year-old headed into the third grade the next fall with high marks. Jo marveled at her boy’s intelligence, loved spending summers teaching him, and would go back to school herself or whatever it took to be able to keep things the way they were until he finished school. She wasn’t at all inclined to delegate this experience to any tutor. Dalton was happy because his family seemed happy.

Then the less obvious concern emerged. It was less obvious to Jo because she longed to be everything her boy required in a companion. Sander made no friends in the crowd of chattering, giggling little people scurrying around him because he couldn’t talk to them. But he made no enemies either. He got along much better with the teachers, that’s all. As he developed physically, the younger male teache

rs in the elementary school had to fight the urge to invite him over for a beer some weekend. The young women secretly wondered how much a kid he could truly be, square-jawed, powerful, and well-spoken as he was. While the kids, they said only, ‘Pick me up, Sander!,’ ‘Swing me!,’ ‘Bet you can’t lift this thing.’ He learned to politely ignore them.

Doris told her daughter again and again that it could not continue that way. It wasn’t healthy. The child had to have friends. He needed to find out firsthand how to interact with his peers.

‘His peers are wetting the bed and eating crayons, mom.’

‘You know what I mean. He’ll be out in the real world in the blink of an eye, running that ranch himself and ...’

‘Not if you let him on the football team, he won’t.’

‘Shut up, Frank.’ Then, to her daughter, ‘Sweetheart, long-term relationships can’t be taught. Not by a mother at least. He has to be able to deal with people. What will he do for friends, skipping grades like that?’

Art provided the answer. Jo smiled at the thought of her boy wielding a paintbrush, expressing himself on canvas, ever since Ms Moffit told her of Sander’s flair for it. She had an easel set up in one of the spare bedrooms and he spent long hours at it. As with all his subjects, he craved every scrap of knowledge available to him. His parents hadn’t an artistic bone in their bodies, so Jo found herself hiring a tutor for Sander after all. He was Jason Markette, a twenty-three-year-old painter with a studio in town. He had shown his work all over Texas and twice in New York. Sort of a local celebrity, this young man.

As with most artists, despite his burgeoning notoriety, Jason wasn’t exactly flush with cash, so he jumped at the offer of a steady gig working with Sander once a week at their home. The spare bedroom with an easel became a full-fledged studio. Paint on the floor, music at odd hours, and the essence of spirits on still air. Jason was respectful and patient with his student. He initially treated Sander like a job. Then he reacted to him as a child. Within a year, it was something else.

Once a week tutoring became twice a week. Those were the paid visits. Jason visited more often as Sander progressed and diverged from his teacher’s style. They talked in a rapid banter. They argued. They insulted and praised one another. Physically, they were the same size. They had a common wit. Their laughter sometimes grated on Dalton’s nerves.

While Jo actively schemed to heed her mother’s advice – taking her boy to the park and playgrounds and the mall, urging him to socialize with other kids he’d passed in school, and those he would soon catch – Sander had found his own friend in Jason, who was a mere three years younger than Jo. Initially, this seemed to bear out Dalton’s doctrine of life as a giant. Let things sort themselves out, you know. Yet, oddly enough, he was the first to feel the itch of resentment.

He hid it well. He knew it was selfish, but when they began working more and more alongside one another in the pastures, he did not especially like Sander coming out with thoughts that sounded as though they should be spoken by Jason. Some were prefaced that way: ‘Jason says ...’ Some were not, but they were Jason’s nonetheless. The man had an annoying habit of speaking in parables.

The danger with parables is in how they’re interpreted by the teller, and how that interpretation is passed along to the listener. Dalton knew this, but he fought to keep his mouth shut and chalk it up to part of Sander’s education. Growing up. He made an admirable job of it until, shortly after his son’s eighth birthday, Jason taught the boy how to shave. Dalton was upset with Jason over that and he told his wife so.

‘Now you sound like me,’ Jo told him. ‘We can’t teach him everything. He’ll pick things up as he goes along.’

‘What else is he picking up from Jason? I’m saying what do we know about this guy?’

‘We know he makes my boy happy. He can paint, we know that. Have you looked at what your son is doing? It’s beautiful.’

‘Yes, I have. I think it’s great. But have you looked at how he’s dressing? The things he says? It doesn’t seem like him sometimes. Sounds a lot like religious talk if you ask me.’

‘Religion strikes you as foolish now.’

‘No, honey, it doesn’t. I’m wondering if you wouldn’t rather be the one to teach that to your boy is all.’

‘Do I come out there and tell you how to build a fence?’

‘Not lately.’

‘Not once. Let me take care of what goes on in here.’

‘Will you at least find out where Jason’s from? Please.’

Jo was angrier with her husband than she let on. He didn’t figure it out until supper that evening. Dalton had always hated beans: beans in general, but specifically limas, pintos, garbanzos, and navy beans. They were the only things you could put on a plate that would raise a complaint from him. After lunch, Jo made a special trip to the grocery store. Supper that night was five-bean salad, pinto and bacon soup, navy beans with rice, and there could have been beans in the pudding for dessert.

‘This is so good, mamma. We never have beans. Why don’t we eat beans more? Jason says beans are brain food.’

‘I’m glad you like it, hon. We might just have them more often. You never know.’

Dalton ate what he could stand and went to bed with a growling wildcat in his stomach. In addition to unintentionally pissing off his wife, he had also succeeded more than he could know in sewing a nagging concern inside her. She began that night cataloging the things she knew of Jason. There wasn’t much. She thought about his lean, wiry figure and unkempt appearance, which she had previously chalked up to the persona of an artist. Did she want her boy to be like that? She remembered that she had smelled smoke on Jason more than once and now she worried that Sander would show up with cigarettes. Or worse. The local news ran stories now and then about designer drugs popping up at parties and football games in Dixon. More and more with every passing day, Sander was looking like a grown man, and acting like one. Still, eight years old is too young to lock horns with serious vice. Maybe he should be riding horses more while they could carry him, and painting a little less.

Jo decided she would check into Jason Markette, find out something more about him than the fact that people seemed to like his work. If what she discovered was benign or irrelevant, she would never tell her boy she’d been snooping. If it went the other way, she’d deal with that when it arose. This marked the first secret she had ever actively kept from Sander, and she didn’t like the feel of it. But she could do this no other way.

For his part, Dalton was formulating a plan. Not so much a plan to meddle; rather, he determined he’d made some mistakes as a father and would set about methodically correcting them. First, it was past the time for Sander to be taking more responsibility over the herd. Will had given Dalton a paid part-time job on the place when he was six. How this had slipped Dalton’s mind on Sander’s sixth birthday he did not know. This very day, a Saturday, when the oversight occurred to him, Dalton dropped a willow tree he had plucked from the bank of the creek, took off his gloves and walked back to the house. He found his son alone, upstairs in the studio.

‘Where’s your mother?’

Without turning from the canvas, Sander said, ‘Went to town. An hour or so ago.’

‘Hey. How does ten dollars an hour sound to you?’

‘Do what?’ Now he looked at his daddy.

‘Ten dollars an hour, twenty hours a week. That’s fair, aint it? Eight hundred dollars a month, working for your old man.’

‘Yes sir, it’s fair. But I don’t know that I want a regular job at this juncture.’

‘What juncture? I don’t know that I’m asking you what you want. You can work five four-hour days, or six threes and a two. It’s up to you. You start tomorrow.’

‘Tomorrow is Sunday. Jason comes on Sunday.’

‘Monday then.’ Sander nodded at him. ‘That’s your best work yet, by the way.’ He pointed at the canvas.

Sander studied it. ‘Jason says it’s stilted

and trite. My colors are muddled to hide inexperience. I might need to trash it.’

‘Don’t trash it before your mother sees it. Please.’ He would’ve liked to muddle Jason’s colors a bit right then. Something occurred to Dalton. ‘Isn’t Sunday the Sabbath?’

‘If God made all days, then they all belong to him. He wouldn’t expect us to live in modern times by the same rules as ancient societies, daddy.’

‘I see. It’s good none of that stuff is written in stone, then.’

On his way back across the pasture, a second thing struck Dalton. It was time Sander learned to drive. This wasn’t as glaring a misstep as the job, because it hadn’t been an issue with Dalton and his daddy. Will didn’t have a truck that would fit him. He went the places he needed to go in his old ranch cart hitched to a two-horse team. There weren’t that many places he needed to go. Now though, Dalton did have a Ford crew cab pick-up with the front seats bolted where the back seats had been removed. It wasn’t comfortable or stylish, but it worked. He always saw his father as somewhat limited by his size, his lack of independence. He didn’t want his son feeling that way. And, if he were able to get out and around from time to time, he might meet other interesting people, pick up some things from them to balance out the Jason monopoly.

This is something which surely had to be discussed with Jo, which got him thinking. Where had Jo gone? She didn’t tell him anything about running errands this morning.

He was nearly to the creek. The willow was all muddy now, spanning the water like a felled bridge. He wished he had carried it to a clearing at least, instead of letting it smack down in the soggy muck. He took his gloves from his back pocket and looked at them. Buckskin. Great gloves, his favorite pair. The first few pairs Jo made were beautiful, but there was something about the fit that weakened his grip when he wore them. They were not quite right. Jo noticed the calluses on his hands growing. They scratched her, and she knew he wasn’t wearing his gloves. Without saying anything to him about it, she sat at her sewing machine and made one new pair a day and handed them to him as he walked through the door in the evening. She would tell him to put them on.

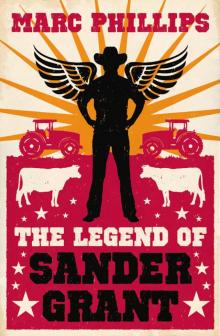

The Legend of Sander Grant

The Legend of Sander Grant